Southeast Asia, winner of the political-economic rivalry between China and the United States

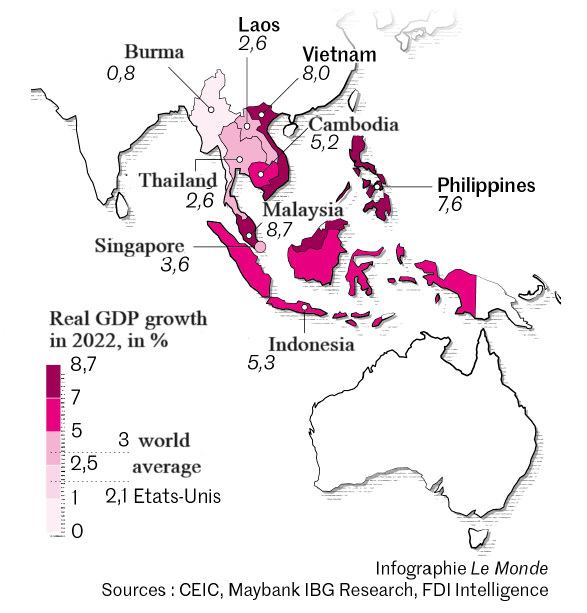

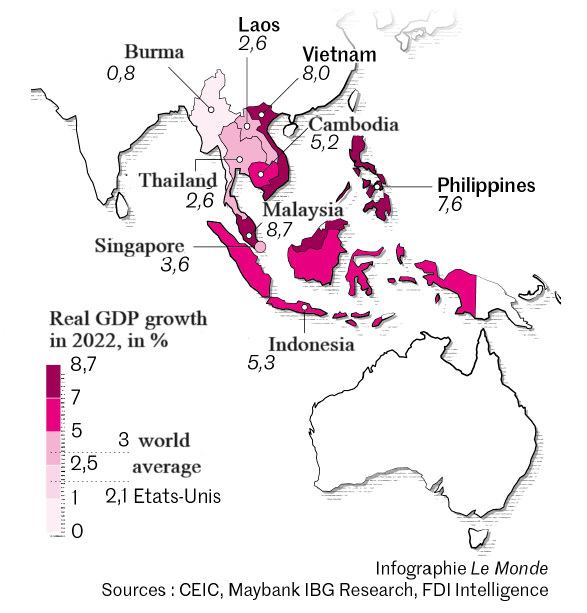

ANALYSIS | Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines are leveraging tensions between the two giants to position themselves as indispensable partners to Western countries.

Mohamed Kamarulzaman believed he had identified a lucrative niche in electronic component manufacturing: supplying polycrystalline silicon to China. A key compound in semiconductors, especially photovoltaic cells. Imported from a producer in the United States, the product was processed in Malaysia and resold in its pure form to China by the startup established in Malaysia by Mr. Kamarulzaman. He previously led the Malaysian semiconductor group SilTerra before its sale to private funds in 2017.

In 2020-2021, the implementation of American sanctions on exports of sensitive products to the Chinese semiconductor industry brought a halt to this activity. “We knew we could be affected. I had no desire to end up with a shipment blocked somewhere,” he recounted in May, in Kuala Lumpur. The complex and changing announcements from the US government had a deterrent effect: “We decided to stop everything, in agreement with our Chinese partner.”

However, “Doctor K,” as the doctor of electrical engineering, found another option. “Around the same time, various Japanese manufacturers established in China were encouraged to leave the country,” he explained. The Malaysian then embarked on manufacturing parts in his country for equipment used in Japan for producing wafers, the substrate material for semiconductor devices such as electronic circuits. “They require high dimensional precision and finish. Therefore, we found Malaysian suppliers from the aviation and aerospace sectors to meet the requirements of Japanese manufacturers. Malaysia remains attractive due to costs,” he justified.

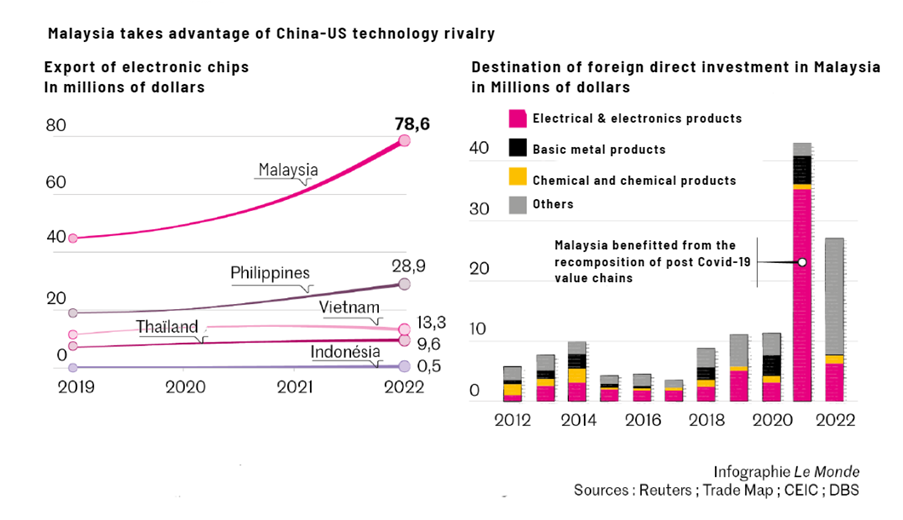

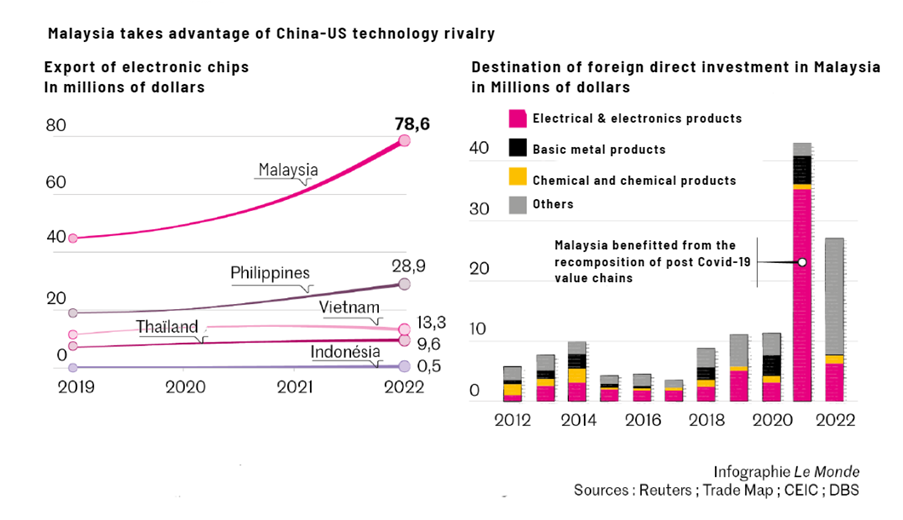

Read also | Malaysia benefits from multinational companies’ derisking with China

The computer revolution, followed by the advent of the Internet and now artificial intelligence, have made semiconductors the centrepiece of technological warfare. These components, particularly the most sophisticated ones, lie at the heart of the United States’ strategy to isolate China through a range of laws and sanctions imposed by the US Treasury.

“China + 1” Strategy

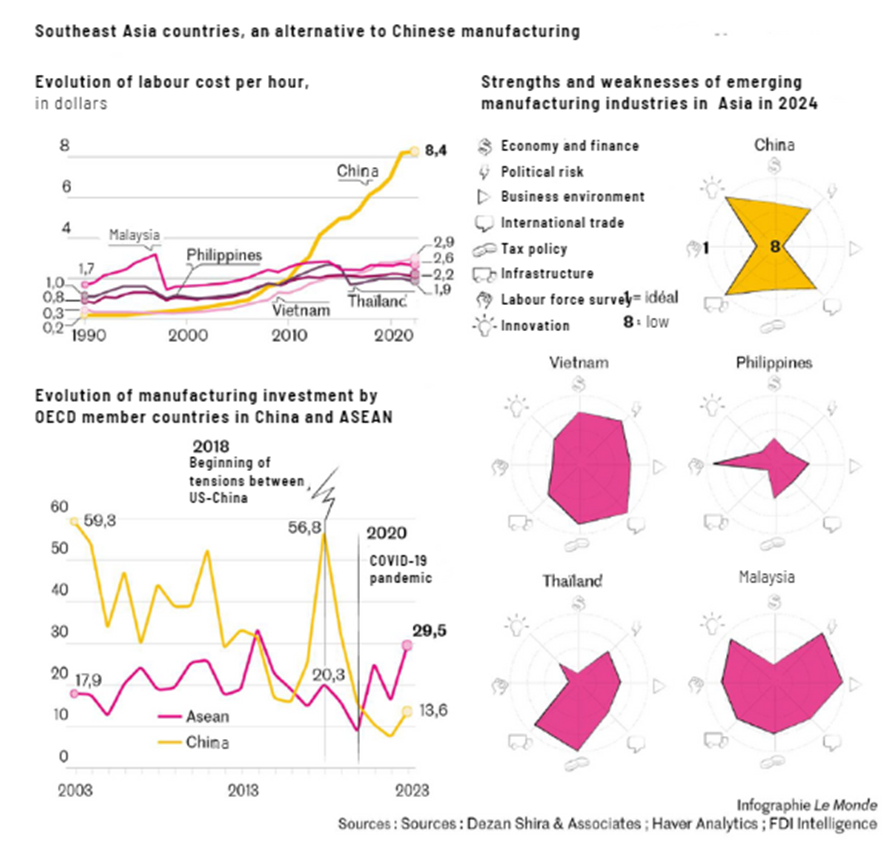

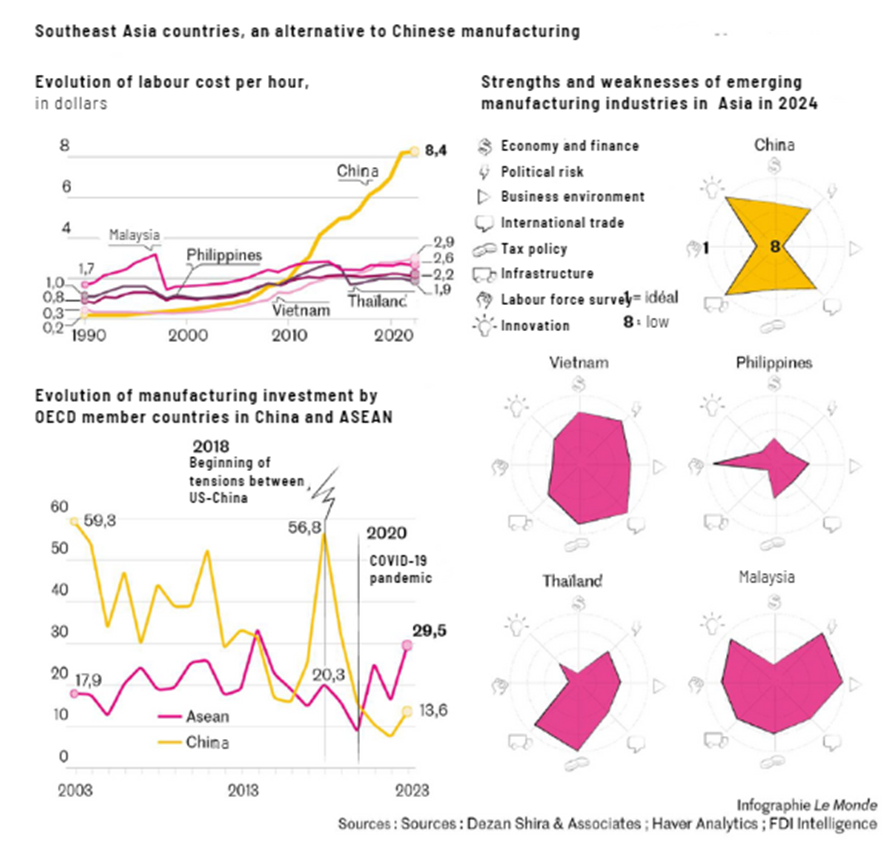

The countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which includes ten member states such as Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand, have developed themselves for the past few decades as the electronic subcontracting industry, and benefiting from relocations led by Japanese, South Korean, and Taiwanese companies. They are well-positioned to strengthen their role as an alternative to China. In multinational headquarters, the focus is on the “China + 1” strategy: “I call it the China + 1, 2, 3, n strategy. It is clear that it redirects investments towards Southeast Asia, particularly in the technology sector. The strategy often involves staying in China for the Chinese market, or moving operations elsewhere for the rest of the world,” explains Marco Förster, ASEAN Director at Dezan Shira & Associates, based in Hanoi and deeply entrenched in the region.

Association of South-East Asian nations (ASEAN) member countries

Read also | Southeast Asia at the heart of the new “great game” between China and the United States

Southeast Asia could benefit from a similar dynamic to what Taiwan and South Korea experienced, along with Hong Kong and Singapore. Thanks to the Cold War in the 1970s-1980s, through American and Japanese relocations, they became global champions in electronics, especially in semiconductors.

“Industrial groups are still in a reactive phase to these new geopolitical requirements. Having to source from a ‘politically correct’ supplier increases costs. ‘Derisking’ from China means having to hold more inventory. Most of the equipment used in industries comes from China, so finding an alternative isn’t easy,” explains David Lacey, the research director of a major European component group based in Penang, Malaysia, and president of several local semiconductor manufacturing associations. “Compared to its neighbours, Malaysia can boast of having a workforce familiar with high technology for two or three generations. For multinational companies, engaging new service providers in Vietnam for testing and assembly carries risks.”

The state of Penang, located in the northwest of the Malay Peninsula along the Strait of Malacca, serves as Malaysia’s semiconductor hub. The island of Penang itself is divided: half is dedicated to seaside and “historic” tourism, including the Chinese heritage city of Georgetown, while the other half hosts factories and laboratories that have spread across the mainland part of the state. This mainland area is connected to the island by two bridges.

Leader of the “back-end”

In 1972, Intel, followed by AMD and Hitachi, established assembly plants in the first free trade zone of Malaysia in Penang. This development made Penang and Malaysia global leaders in the “back-end” phase of semiconductor production. This phase, while less complex, remains crucial as it involves slicing silicon wafers and inserting chips into packages, followed by testing. Malaysia’s specialisation in this area has secured a 7% share of the global semiconductor trade market, ranking 9th globally, and a 13% share specifically in the “back-end” segment. Within ASEAN, only Singapore surpasses Malaysia with an 11% share in the global semiconductor trade market, primarily due to its “front-end” foundries, which handle the upstream manufacturing process involving the lithographic fabrication of chips on wafers — the most sophisticated and expensive step in semiconductor production.

Read the analysis | The global semiconductor map redrawn in 2024

Half an hour by highway from Penang, the Kulim high-tech park, an extension of the “Silicon Valley of the East” as Penang is referred to, in the neighbouring state of Kedah, is undergoing significant expansion. “Land costs here are 25% cheaper than in Penang. We are opening a fourth phase,” says its president, Mohd Sahil Zabidi, who aims to attract international hotels and educational institutes. Currently, such facilities are predominantly concentrated in Penang.

Since its opening in 1996, the number of “tenants” at the park has increased from 30 in 2019 to 49 in five years’ time. Among them, four fabs, semiconductor fabrication plants that require specific infrastructure for water and waste treatment. In 2023, one of these fabs, the German semiconductor manufacturer Infineon Technologies, announced an additional investment of 5 billion euros over five years to expand its production capacity at the Kulim site. They produce 200-millimeter power chips for six major automotive clients, including three in China. Malaysia has thus become its primary production base worldwide.

Advantageous fiscal policy

Benefiting from its experience, this country of 34 million inhabitants has successfully implemented policies involving local and regional public assistance. Penang and Kedah offer industrial setup times not exceeding ten months, along with one of the most advantageous fiscal policies. Electricity is inexpensive there but remains heavily carbon-intensive, a concern voiced by multinational companies constrained by their climate obligations.

10.2 billion

Of dollars, the cumulative investment of Google, Microsoft and Amazon in the cloud and artificial intelligence in Malaysia by 2030

Malaysia has long faced the challenge of moving up the value chain: “back-end” activities downstream generate less added value than upstream. Penang, which employs 300,000 people in the semiconductor industry, is nearing saturation and is now striving to be more selective.

“We are selecting projects. We avoid those that rely too much on labour,” shared by Loo Lee Lian, CEO of InvestPenang, the agency responsible for foreign investments.

While fabs are starting to set up in Kulim, Penang benefits from increasing sophistication in the ‘back-end’ sector, especially in the industries like electric vehicles use an average of 50 chips and sensors per vehicle. “We test the functions of the chips and sensors, then ship them out. This is the final stage before the product is used by the customer. It’s extremely important,” emphasizes Yap Thoong Poh, the general manager of Bosch’s new factory opened in August 2023 in Batu Kawan, a new development area on the mainland part of Penang.

In the “box”, the sterile section of the factory as white as a hospital, Bosch tests the latest generation chips and sensors manufactured in Dresden, Germany. Penang has become its most advanced testing facility in Asia, surpassing those in Germany, Hungary, and China. However, across all its operations, the German equipment manufacturer employs only 4,000 people in Malaysia compared to 42,000 in the United States and 58,000 in China – the world’s largest automotive market.

Diversify and strengthen the global value chain

If diversification away from China benefits Malaysia due to its experience, it is clearly sparking interest among its neighbours. Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand, the four other most advanced economies in the region, are also aiming to capitalise on this trend. They could even benefit from the U.S. legislation, the Chips and Science Act, signed in August 2022 by President Joe Biden to reindustrialise the United States in the semiconductor sector. This legislation includes, among other things, allocating $39 billion (36 billion euros) in public funding to promote semiconductor production on American soil.

If, in theory, this subsidy fair, since imitated by Europe and Japan, risks depriving certain countries of investment, it is seen in South-East Asia as likely to benefit assembly activity, under -contracting and testing – especially in countries with a trained but less expensive workforce, such as Malaysia. “Not only has investment not decreased since the Chips and Science Act in Southeast Asia, but it has continued to increase, with no signs of slowing down,” notes Marco Förster.

This is especially true for countries expected to benefit from the International Technology Security and Innovation Fund, a component of the Chips and Science Act that allocates $500 million over five years “to diversify and strengthen the global semiconductor value chain among allied countries.”

Three out of the five “partner” countries selected at this stage are in Southeast Asia: Vietnam leads the pack, followed by Indonesia and the Philippines, which are emerging as new pillars of the U.S. government’s “friendshoring” strategy, or the relocation from China to friendly countries. Malaysia and Singapore have already proven themselves in this regard. “Everything indicates that Asia will remain the primary outsourcing hub for the global semiconductor market, and that the American and European Chips Acts could accelerate the ongoing redistribution of these activities, to the detriment of China and Taiwan, and to the benefit of new players such as Vietnam, the Philippines, and India,” wrote the French consulting firm Global Sovereign Advisory in an October 2023 report on semiconductors.

Vietnam, a relatively new player in the “back-end” sector since its first assembly and testing factory, an investment by Intel, opened in 2010, is clearly ramping up its efforts. The country aims to invest around 1 billion dollars in training 50,000 semiconductor engineers by 2030. This is a challenge to be taken seriously: in just over a decade, Vietnam has risen to become the world’s second-largest exporter of smartphones, behind China.

Also read: Vietnam, the little dragon dreaming of becoming an economic alternative to China

While American company Amkor and South Korean Hana Micron inaugurated new semiconductor factories in Vietnam in 2023, Intel postponed an initial expansion project there. According to anonymous sources cited by Reuters, this was due to “excessive bureaucracy and instability in electricity supply.” Intel appears to prefer Malaysia, where it already employs 10,000 people. The company plans to invest $7 billion over the next decade in Kulim and Penang, particularly in a factory dedicated to a new chip stacking assembly technique aimed at enhancing their performance.

Brice Pedroletti

Penang (Malaysia), special envoy

Source: Le Monde (Printed copy)

Disclaimer:

The English version is a translation of the original in French for information purposes only. In case of a discrepancy, the French original will prevail.