Time is ripe for Malaysia to move upstream into designing chips

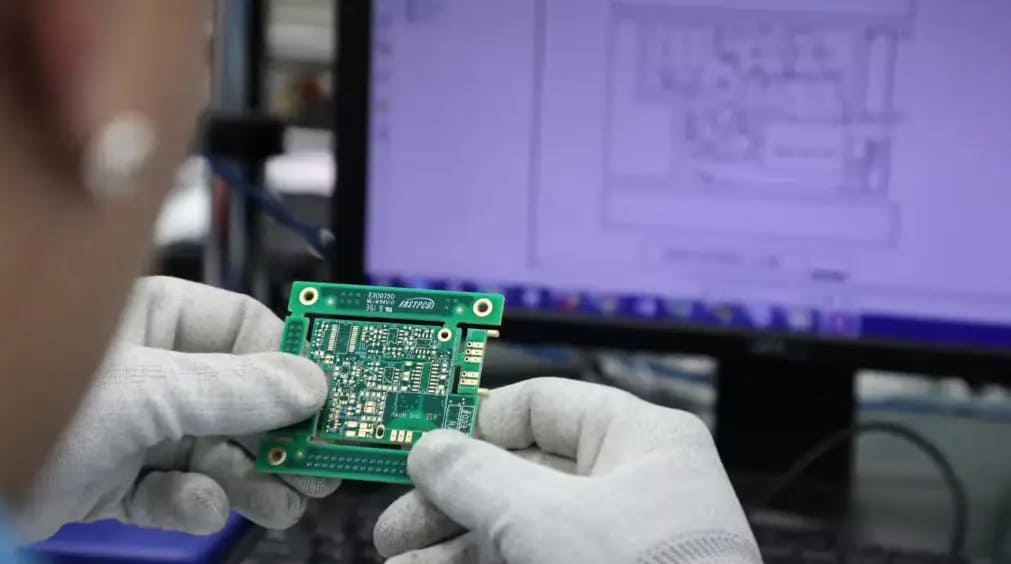

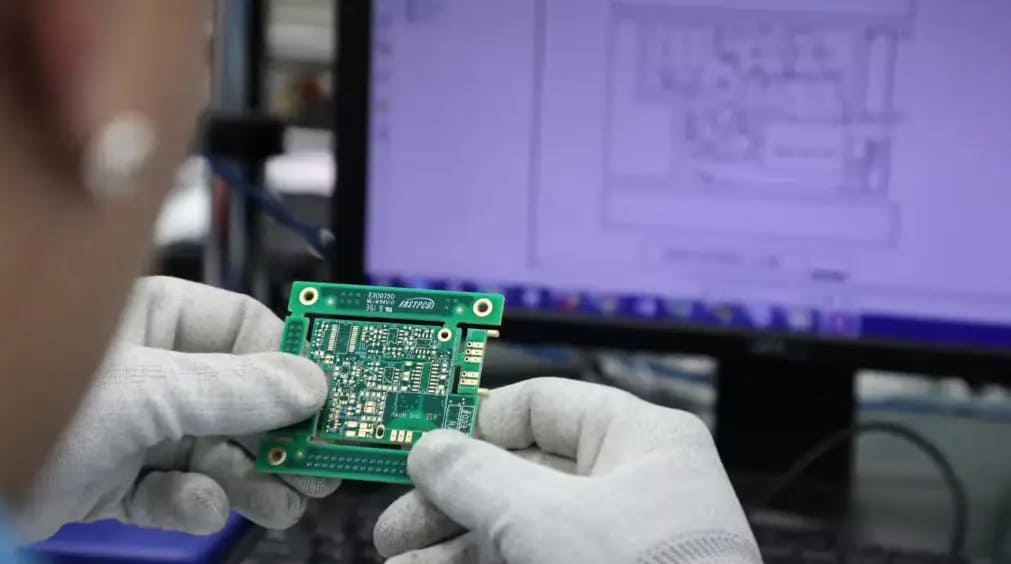

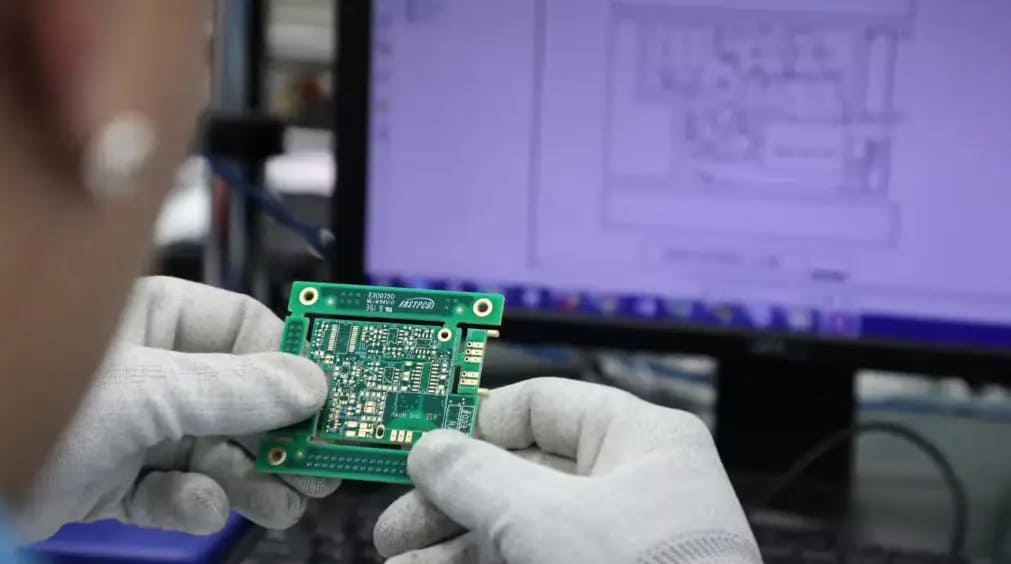

An employee inspects a printed circuit board at a production facility of automated test equipment designer Aemulus Holdings in Penang, Malaysia. © Reuters

Wee Chian Koh is an economist with the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office in Singapore. Marthe M. Hinojales and Hongyan Zhao are senior economists with the organization.

April 11, 2024 — The increasingly heated struggle between the U.S. and China for dominance in semiconductor technologies has been a godsend for the Malaysian island of Penang.

These days, Penang’s industrial parks are abuzz with traffic and construction activity. Thanks to its well-established electrical and electronics manufacturing ecosystem, good connectivity, reliable infrastructure and its skilled and multilingual workforce, Penang has in recent years won new chip sector investments from multinationals, including Lam Research, Infineon Technologies, Texas Instruments, Micron Technology, Bosch, Advanced Semiconductor Engineering (ASE) and Intel.

These investments have reinforced Malaysia’s entrenched position in the late stages of the semiconductor supply chain, particularly chip assembly, testing and packaging, areas in which it holds a 13% share of the global market.

This is a lower stakes, lower profit and lower profile end of the business than the design and production of semiconductor wafers, activities currently centered on the U.S. and Taiwan, respectively.

Thus, the government of Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has set its sights on taking Malaysia’s chip industry upstream as part of its New Industrial Master Plan 2030, unveiled last year.

In January, the government set up the National Semiconductor Strategic Task Force to focus on investment incentives and manpower issues. A key element of the government’s strategy is to raise the technological level of Malaysian manufacturing as a way to bring up wages so that skilled workers are less tempted to go overseas.

Yet Malaysia will face heavy competition in trying to move upstream in chip production.

With the help of attractive tax incentives, Vietnam has convinced U.S. companies, including chip design software maker Synopsys and packaging and testing company Amkor Technology, to expand their local operations. In February, India approved plans by Taiwan’s Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing to launch an $11 billion joint venture chip fabrication plant that will be the country’s first. Singapore, which is already home to several fabs, is drawing new interest from companies such as Taiwan’s Vanguard International Semiconductor.

Wafer fabrication is a challenge because of the massive costs involved in setting up a foundry, especially for next-generation chips, and the scarcity of key talent. One Malaysian business group estimated two years ago that Penang faced a shortage of 50,000 engineers to meet semiconductor industry demand. Meanwhile, government data shows that fewer students are pursuing studies in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Policymakers should review the strategies they used in past decades to help bring downstream chip production plants to Malaysia. Industrial master plans obliged multinationals setting up factories to transfer skills and technologies, and to work with local suppliers. Business and government, meanwhile, worked together to set up the Penang Skills Development Centre to boost workforce talent.

The resulting self-reinforcing ecosystem of chip packaging, testing and assembly companies led, in turn, to opportunities for automated equipment and services, and put local companies, including Inari Amertron and Greatech Technology, on a growth trajectory.

Advanced packaging techniques to enhance performance and functionality now represent a good opportunity for Malaysia to advance to the leading edge of semiconductor technology. Intel has already committed to build its first overseas facility for advanced 3D chip packaging in Penang.

Chip design could be a more promising area for Malaysia than fabrication. A few local companies, such as Oppstar Technology, can already provide design services for advanced chips.

However, chip design is knowledge-intensive and has high barriers to entry. To create a cluster of homegrown chip design houses, strong collaboration among industry players, government and academia will be needed to foster entrepreneurialism, encourage innovation and develop talent.

Thanks to its well-established electrical and electronics manufacturing ecosystem, Penang has in recent years won new chip sector investments from multinationals, © Reuters

The rapid adoption of advanced technologies and the increasing complexity of semiconductor devices are driving demand for custom design services. Malaysia must quickly seize opportunities in chip design to move up the semiconductor value chain as competition intensifies.

Industry players can work with tertiary institutions to set up centers of excellence for chip design and develop internship programs to expose students to industry-standard design projects. The government could support universities and technical institutes by providing advanced electronic design automation tools and offering matching grants to startups for design-related investments.

It will also be important for the government to see through plans to revamp the country’s Technical and Vocational Education and Training system to add more high-tech courses and make the program more attractive to both prospective students and employers. Officials are also mulling a proposal to allow foreign students in engineering and technical fields to stay on to work in Malaysia after graduation to ease the talent shortage.

Malaysia has an opportunity to make an impact in some niche areas of chip fabrication. Germany’s Infineon, for example, is building a next-generation silicon carbide power chip fabrication plant in Kulim, near Penang. This could position Malaysia as a regional hub to meet the rising demand for power semiconductors for electric vehicles, data centers and renewable energy systems. SilTerra Malaysia, meanwhile, is producing another kind of chip for data centers, known as silicon photonics, in Kulim.

Malaysia’s strategic diplomacy and economic foresight have shaped its semiconductor landscape over the past few decades. Today, the country is emerging as a front-runner in the reconfiguration of the global chip supply chain.

However, amid intensifying competition, the strength of Malaysia’s chip industry resurgence will hinge on its ability to move closer to the technological frontier and away from labor-intensive, low-value stages of production.

Source: Nikkei Asia