Aiming for Upstream Processes, but Facing Many Challenges – ASEAN’s Semiconductor Attraction Efforts Heat Up

This is the fourth in a series reporting on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)’s efforts to attract semiconductors amid a deepening US-China conflict over high technology. So far, we have looked at the potential of each country. However, there are a number of issues that need to be resolved, including a shortage of human resources, in order to take on greater added value in the upstream process. [Tetsuo Sakabe]

According to Semiconductor Equipment and Materials International (SEMI), headquartered in California, the semiconductor market is expanding due to rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and the spread of electric vehicles (EVs), and the global market size is expected to reach USD1 trillion (approximately 157 trillion yen) by 2030, an increase of about 70% compared to 2022.

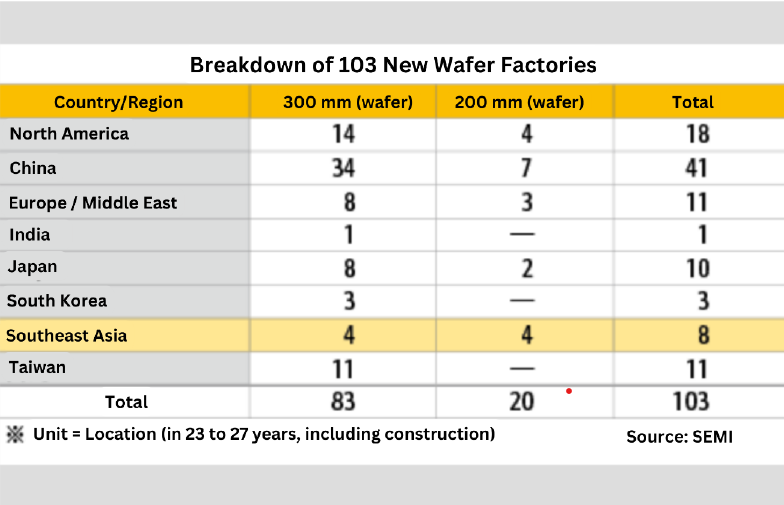

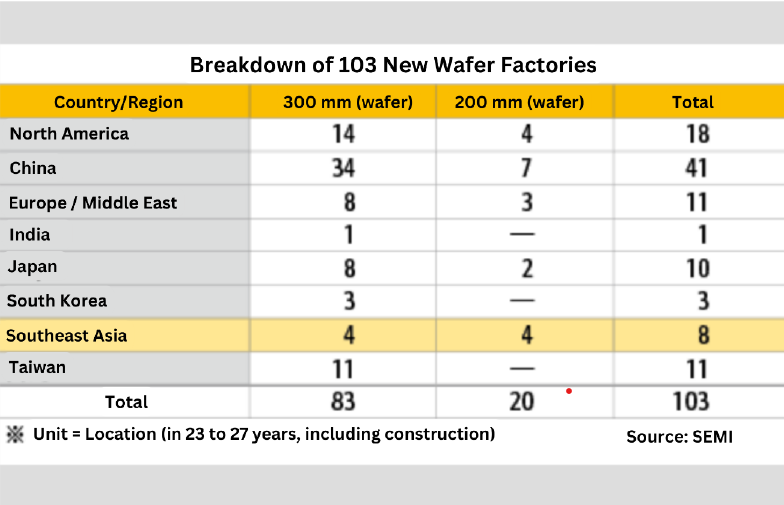

To achieve this, the construction of wafer (substrate) factories is essential. SEMI estimates that a total of 103 new wafer factories, including those currently under construction, will be built around the world between 2023 and 2027, combining 8-inch (200 mm) and 12-inch (300 mm) diameter wafer factories.

From this, Asia accounts for 70% of the total, with 74 locations. China leads with 41 locations, followed by Taiwan with 11, Japan with 10, South Korea with 3, and India with 1. Southeast Asia has 8 locations, with 4 locations each of 300 mm and 200 mm.

According to SEMI Chief Executive Ajit Manocha, more than 50 additional wafer fabs will be needed by 2030 to support the world’s digital transformation (DX).

Ajit expressed hope that “growth in Southeast Asia can mitigate disruptions to supply chains,” but warned that “to grow, we need to seize the opportunities.”

Malaysia is ambitious

MSIA Chairman Wong responds to an interview on May 29, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Photo by NNA)

Malaysia is one of the Southeast Asian countries that is showing a strong desire to attract semiconductor-related investment. In an interview with NNA, Wong Siew Hai, chairman of the Malaysian Semiconductor Industry Association (MSIA), said, “Malaysia has a semiconductor industry foundation that has been built up over 50 years. We would like to attract the country’s first 300mm wafer factory in about three years, when the next investment cycle arrives.” He believes there is potential not for cutting-edge semiconductors, but for mature semiconductors with circuit line widths of 28 nanometres (nano is one billionth of a meter) to 14 nanometres.

Dato Loo Lee Lian, CEO of the InvestPenang in the state of Penang, where semiconductor back-end processing is concentrated, is enthusiastic, saying, “The island of Penang has become cramped, but on the mainland there is plenty of land, water and electricity needed for front-end processing.” In 2023, RM60.1 billion (approximately 2 trillion yen), equivalent to 47% of manufacturing-related foreign direct investment (FDI) into Malaysia, was concentrated in the state. Using the phrase “dual supply chain,” CEO Loo also said, “We want to maintain neutrality between the U.S. and China while also focusing on accepting Chinese companies.”

Investment Penang CEO Loo responds to an interview on May 30, Penang, Malaysia (Photo by NNA)

According to a report by the New York Times, AT&S, a major Austrian printed circuit board (PCB) manufacturer that established its first manufacturing base in Southeast Asia in Kedah, northern Malaysia, in January this year, had also considered Thailand and Vietnam as potential locations for a “China Plus One” initiative to reduce dependency on China. However, it appears that the deciding factors for the company’s expansion into Malaysia were the well-developed electronics ecosystem, as well as:

- tariff exemptions and preferential tax treatment within the free trade zone

- a stable government

- and a large number of English speakers.

MSIA Chairman Wong said of Singapore, “Due to its small land area, there is a limit to the construction of more wafer factories.” He also said that Vietnam has “many low-tech industries that are relocating their bases from Malaysia to Vietnam in search of cheap labour,” and stressed the need to differentiate itself from Vietnam by increasing added value in the future.

As far as SEMI knows, there are no wafer factories scheduled to be completed in Thailand by 2027. However, Chairman Wong described Thailand as a “dark horse.” Although Thailand does not have the flashy performance of Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, who announced the National Semiconductor Strategy (NSS) to promote the semiconductor industry at the semiconductor exhibition “SEMICON Southeast Asia 2024” held in the capital of Kuala Lumpur, Thailand has an electronics foundation and is likely to be able to attract semiconductor companies in the future. According to the Board of Investment of Thailand (BOI), Thailand attracted a record 800 billion baht (approximately 3.4 trillion yen) in semiconductor-related investment in 2023.

The challenge is to develop highly skilled human resources

The biggest bottleneck for Southeast Asia in attracting wafer factories in the future is the development of highly skilled human resources. For example, an average of 2,000 specialised personnel are required for one wafer factory. The importance of human resource development was emphasised at every opportunity during speeches and seminars held at SEMICON Southeast Asia 2024.

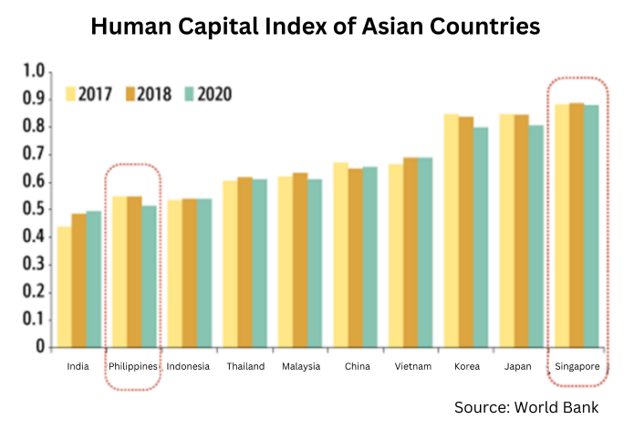

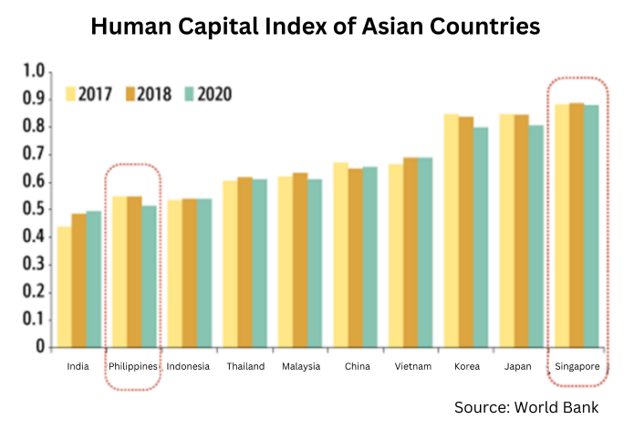

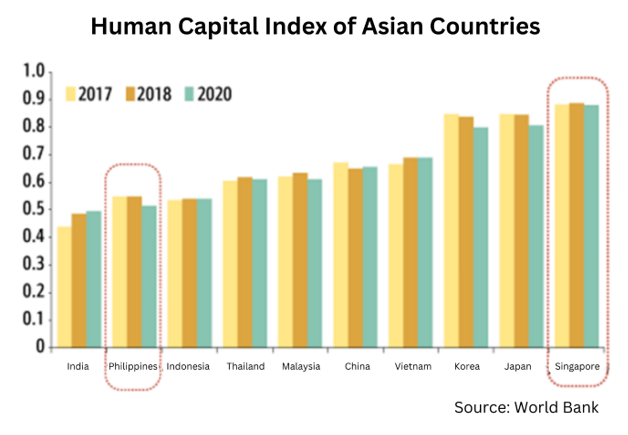

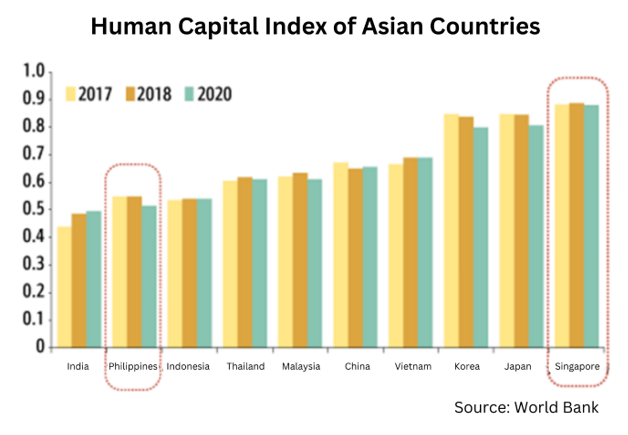

British research firm Oxford Economics cites “abundance of highly skilled human resources” as one of the reasons why Singapore, which started out as a back-end processing centre like Malaysia and the Philippines, has come out on top. In the “Human Capital Index 2020” published by the World Bank, Singapore tops not only Asia but the world, surpassing Japan and South Korea. The Human Capital Index is an index that measures the human capital that a child born today will have accumulated by the time they turn 18, taking into account the country’s health and education situation.

Singapore is also a magnet for talent from neighbouring countries: According to Oxford Economics, Malaysia produces 5,000 engineers each year, many of whom move to Singapore in search of higher salaries.

Itsuko Ago, director of the Kuala Lumpur office of the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), said of Malaysia, “It will take time for the country to transition to advanced industries such as front-end processing. The country has a shortage of R&D personnel, which makes it difficult to take advantage of its relatively low labour costs compared to Singapore.

Vietnam is also facing a serious labour shortage. There are currently only about 5,000 skilled workers, and it is said that the number needs to increase by at least 50,000 by 2030. The Vietnamese government’s efforts to address this problem have only just begun.

Ryotaro Hagiwara, director of the JETRO Hanoi office, points out, “I get the impression that they are relying on foreign governments and companies, including the United States, South Korea, and Japan, for support in areas including technological development and human resource development.” He also says that the electricity infrastructure is insufficient.

Director Hagiwara said, “Rather than just targeting upstream processes, we first need to have a vision from the Vietnamese government and improve the production environment to determine which semiconductor processes and materials we should focus on developing as our strengths.”

The Philippines faces challenges in terms of neutrality

According to Oxford Economics, the Philippines, which has a higher proportion of semiconductor-related exports than neighbouring countries, like Singapore and Malaysia, has an overwhelming advantage over Vietnam and Thailand in terms of the number of English speakers, but maintaining neutrality is a challenge.

The Philippines is vulnerable to geopolitical influences, and it tends to swing between pro-American and pro-Chinese whenever there is a change of government. The World Bank’s human capital index is also relatively low compared to neighbouring countries. It is also said that there are many areas where intellectual property rights (IP) protection is insufficient compared to Singapore and other countries.

However, even in Singapore, the gap between Taiwan and South Korea, which manufacture cutting-edge logic and memory semiconductors, is not small. AT Kearney, a major US consulting firm, has created a ranking of front-end attractiveness for each country and region, taking into account factors such as highly skilled human resources, government support, and infrastructure. Singapore, which has the most developed semiconductor ecosystem in Southeast Asia, is classified as a “high-end alternative in Asia,” just like Japan. The analysis pointed out the difference between “Taiwan and South Korea” by stating that the costs of factory operations and other factors are a burden.

On the other hand, countries such as Malaysia, India, Vietnam, and Thailand are classified as “low-cost hubs,” and it is recommended that they differentiate themselves from other countries through incentives and improve their business environments.

In the next and final instalment of this series, we will present an interview with SEMI Chairman and CEO Ajit Manocha and SEMI Southeast Asia Representative Linda Tan.

Source:

Disclaimer:

The English version is a translation of the original in Japanese for information purposes only. In case of a discrepancy, the Japanese original will prevail.